Community Carbon Children’s Sermons

by the St. Andrew Lutheran Community Carbon Team

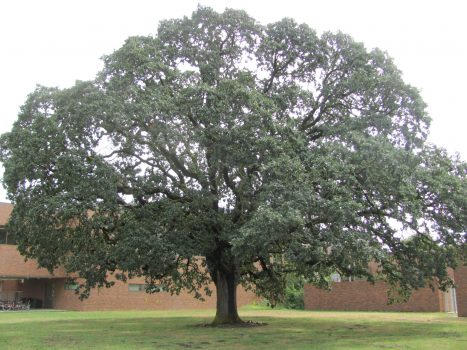

The Oregon White Oak

Good morning, boys and girls. My name is Eric Luttrell. Today I will be offering the first of five children’s sermons presented by our Community Carbon yard science team about some special native plants. Native plants are special. They developed in our regional environment, with plants and animals evolving together to develop mutually beneficial relationships. Insects, birds, and mammals evolved interacting with a very large variety of plants, eating those plants and helping those plants with pollination and see dispersal.

My sermon today is about our native Oregon Oak trees. I am standing here beside Faith, one of two Oregon Oak trees that we recently planted. We are calling the second oak tree Hope. These trees will be the large canopy trees of our Reformation Earth Garden. As they mature, these canopy trees will shade large areas of understory trees and shrubs. We are lucky that we have this large area around our church to plant oaks, as they would become too big for planting in the yards around your house.

To give you an idea about how big Oregon Oak trees can get, this is a photo of an Oregon Oak tree in LuAnn Staul’s yard, so large that not all of it fits in the photo. That’s me standing next to it. This tree is five feet in diameter, about 50 feet tall, and about 300 years old. 300 years ago, when this tree was a sapling like Faith, our United States was just a small colony of the United Kingdom, consisting of 13 sub-colonies located right along the eastern shore of North America. At that time, there would have been no white Europeans in Oregon for at least 50 more years, which was also the time that we declared independence from that United Kingdom.

Oaks of this size and age will be the direct ancestors of many generations of oak trees in an oak grove of many acres. I call them Grandparent Trees. The trees descending from the grandparent trees depended upon someone planting their seeds — what we call acorns. Who does the planting of those acorns? Squirrels. Squirrels like to dig holes and bury acorns for food for next winter. And, amazingly, they remember where they buried those acorns. They remember most of them. If they forget, those acorns will sprout and grow into new oak trees. This means that the oaks and squirrels have a symbiotic relationship—a relationship of mutual benefit. The oaks feed the squirrels and the squirrels plant the oak seeds.

Now why, specifically are we planting Oregon Oaks? Scientists have discovered that oaks in general are the most important trees upon which caterpillars feed. Caterpillars are the larval stages of butterflies and other insects that feed on tree leaves. And millions and millions and millions of caterpillars are collected every spring by adult songbirds to feed their baby chicks. And the best oak trees for hosting caterpillars are native oak trees, and Oregon Oak is our native oak tree.

While our newly planted Faith and Hope look like tall sticks now, when the young children in our church are in high school, they will be 25 to 35 feet tall, as tall as the back side of the sanctuary. Now it will take some time for our two small oak trees to grow large enough to supply lots and lots of caterpillars for baby birds. While we are waiting, the next best trees for caterpillars are native willow trees. And, lucky for us, we have several hundred native willows in the wetland on our property.

Besides caterpillars to feed baby birds, what else do oaks provide for wildlife? Acorns. All kinds of animals eat acorns—squirrels, chipmunks, birds, and deer.

In Oregon and California, the indigenous people (Indians) ate lots of acorns as a nutritious source of fats and carbohydrates. They would leach out the bitter tannins in the acorns, grind them into flour, and make a kind of bread. Since Oregon Oaks were the most common tree in the Willamette Valley (with millions of trees), and since the long-lived oaks had lots of acorns (millions and millions of acorns), acorns were an important native food source along with fish, meat, berries, and mushrooms.

Faith and Hope are the first of many trees, shrubs, flowers, and grasses that we will plant in this area around me just outside our back patio. We intend to call this area our Reformation Earth Garden. With time, this garden will be the home of more than 40 different varieties of native plants. And because most of these 40 new varieties are different from the many, many varieties of native plants currently found in our wetland and forest, we are greatly expanding the diversity of our local ecosystem.

We will be planting these native plants as part of our responsibility to improve our environment for all living creatures. With time, we hope that this garden will become part of what Douglas Tallamy in his book Nature’s Best Hope calls America’s Homegrown National Park, with a variety of native plants in every yard.

- By Eric Luttrel, Community Carbon Team Member at St. Andrew Lutheran Church

The Snowberry

Good morning. My name is Carol, which means song of joy, and I’ll be talking to you today about the Snowberry plant. The Latin name for Snowberry is Symphoricarpos albus.

“Symphori” means bear together, and you can see how the snowberries hang together in a clump. “Carpos” means fruits, referring to the clustered fruits, and “albus” means white, without luster. The berries are a dull white, not shiny. The common name of this plant, Snowberry, also refers to the white fruits.

The plants bloom in the spring from mid-May to July with small white and pinkish flowers that attract hummingbirds, but these natives are mostly pollinated by bees.

When I did research for the Snowberry, I learned that the fruits of this plant are called drupes. I didn’t know that word, but it means that they have a fleshy fruit surrounding a large seed, like in a peach or a plum. Of course, Snowberry seeds aren’t that large because the berries are so small.

Symphoricarpos has about 15 different species, 12 of which are found in the United States, from southeast Alaska to southern California and all across the northern U.S. and Canadian provinces. Snowberries usually grow 3-9 feet tall and are sometimes known as Waxberry, White Coralberry, or White, Thin-leaved, or Few-flowered Snowberry.

You might wonder why there is so much fruit on the plant still, so late in the fall. Well, I grew this plant at my house in Northern Illinois for about 15 years. I planted them because they are native and they would produce berries for the birds. And I can tell you that the berries last through most of the winter into spring. The reason for this is that they have a kind of bitter taste, so it’s not the favorite berry for some of the animals that feed on it.

But the good thing is that the berries stay on the plant into spring so there is food all through the winter for the animals.

Common Snowberry has long been grown as an ornamental shrub. Winter is its most conspicuous season, when its white berries stand out against leafless branches. Its dainty pinkish flowers are also attractive in the spring.

Where can you find this plant? Snowberries are found along stream banks, in swampy thickets, and in moist clearings and open forests. St. Andrew has all of those environments in the Sanctuary of the Firs and the grounds around the church.

Snowberries tolerate poor soil and neglect. I can do that! One of the great things about growing this plant is that it does best in heavy clay soils. I have a lot of that where I live!

Who/what eats this plant? Answer: birds (robins and thrushes, grouse, sort of a brown chicken), deer, antelope, Bighorn sheep, and bears. My research tells me that “use by elk and moose varies.” I’m not sure what that means and don’t know how to ask Bullwinkle Moose the question! Snowberries are also important for providing shelter and food for small mammals.

Various indigenous peoples used the Snowberry for medicine. They created an infusion by soaking the plant in water to make an eyewash for sore eyes. They rubbed the berries on the skin to treat burns, rashes, and sores. They created a decoction of the roots and stems to treat urinary problems, like having trouble peeing. The same decoction treated people for tuberculosis and fevers associated with teething.

Some indigenous groups made brooms out of Snowberry branches, another group hollowed out the twigs to make pipe-stems, and people of one tribe ate one or two of the berries to settle the stomach after eating too much fatty food.

There is another kind of Symphoricarpos that is native in Nevada and California. Because of climate change and global warming, that means it is moving north into Oregon as a native plant. This kind is Symphoricarpos mollis, meaning creeping. It grows low to the ground.

I planted this variety about 2 years ago and the two plants looked really good last year, but one of them kind of disappeared this year. I thought at first it was because of the drought, but after a few weeks I found out the real answer.

I have a black and white cow-print kitty. She is very cute and lovable. She was adopted out of a storm sewer in southwestern Illinois, where she liked to sit with the kids waiting at the bus stop. They named her Maisy.

She likes to help me garden and follows me around doing yard work. She also likes to take dirt baths. You can see in the picture how dusty her black fur gets. Usually, she just takes her dust baths in a dusty area or if she needs a good scratch she does it on the concrete. But I caught her in the front yard giving herself a rubdown on the twigs of that dying Creeping Snowberry! Some of the twigs are still in the yard, but I had to put a white towel under them to take a picture!

How do you propagate Snowberries or get more of them? You can take cuttings of half-ripe wood in July or August or of mature wood in winter. Suckers may be divided in the dormant season. Plants re-sprout from rhizomes after a fire. Common Snowberry spreads by root suckers and is best given plenty of space to create a wild thicket.

Snowberry tolerates poor soil and neglect. I can do that, but I’ll need to put in a barrier for dirt-bath kitty! These native plants are great for controlling erosion on slopes, for restoration after forest fires, and for mine reclamation projects. They are also popular in rain gardens.

- By Carol Harker, Community Carbon Team Member at St. Andrew Lutheran Church

The Oregon Grape

Good morning. My name is Larry Bliesner and I’m here to talk about a native plant. A native plant is one that is natural to our area. My plant is the Oregon Grape, which is Oregon’s State Flower.

The Oregon Grape is actually an evergreen shrub. The tall variety grows 5-8 feet high. The low variety grows to about 2 feet. The Oregon Grape has yellow flowers in the spring, which hummingbirds like. During the summer the plant forms bluish-black berries which other birds like.

The Oregon Grape is not a true grape like the ones we eat. However, Kalapuyan indigenous peoples ate the berries, which are sour. The bark could be used as a yellow color to dye native baskets, while the berries produce the color purple.

The Oregon Grape tolerates shade or sun. It is a good plant for your soil garden and for St. Andrew’s “homegrown” National Park.

- By Larry Bliesner, Community Carbon Team Member at St. Andrew Lutheran Church

The Indian Plum

Hello, I am LuAnn Staul. You may know me as Henry and Penelope’s grandma.

I want to introduce you to another native plant, the Indian Plum The Indian Plum’s scientific name is Oemleria cerasiformis and it has many common names, including the osoberry, Oregon plum, Indian peach, and bird cherry. This plant grows along the Pacific Coast of North America in British Columbia, Canada, Washington, Oregon, and Northern California.

The fruits of the Indian Plum can be eaten and look like clusters of small plums which are dark blue when ripe.

This plant is especially important to pollinators. Pollinators get food in the form of energy-rich nectar and protein-rich pollen from the flowers they visit. Birds, bats, bees, butterflies, and beetles are all pollinators. Once the pollinator has visited a flower it carries the pollen to other flowers; this makes it possible for the pollinated flowers to develop and produce seed.

Pollination is required to produce many of your favorite foods—apples, pears, cherries, and blueberries. Pollinators also support our ecosystem and natural resources by helping plants reproduce.

The Indian Plum is especially important because it is one of the first plants to leaf out and develop flowers. It develops leaves and flowers in early March before many other plants begin to flower. This provides an early source of pollen for bees and other pollinators.

The indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest included Indian Plum fruit in their diets, and they used the plant’s bark and twigs to make tea and medicine. The fruit is also eaten by small mammals like mice and voles, plus foxes, coyotes, deer, bear, and many bird species.

Indian Plum is a tall shrub growing up to 15 feet high. It has multiple trunks that grow upright. The flowers are white and whitish green. The fruit occurs in clusters and is orange and yellow when young but blue-black as it ripens. The plant grows in part to full shade in soil that is dry to moist.

Planting native plants like the Indian Plum provides food for pollinators as well as other native animals. If we all begin adding these plants to our years, we will be on our way to develop a Homegrown National Park in our community.

- By LuAnn Staul, Community Carbon Team Member at St. Andrew Lutheran Church